Our domain or analysis models view the world as objects that interact by exchanging messages.

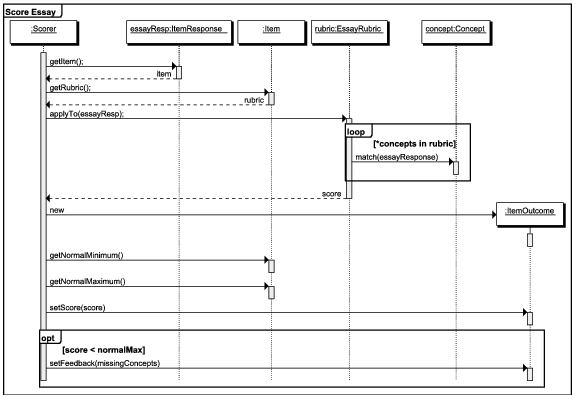

Here is a sequence diagram for our "Score Essay" use-case. To help understand this, we’ll take this apart, one element at a time, looking at what each one shows us.

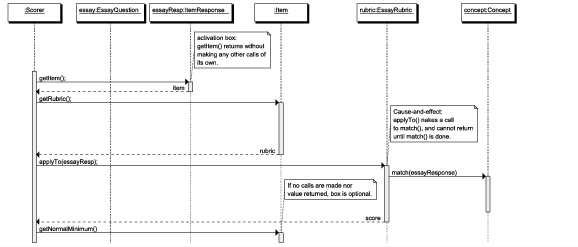

If it seems confusing to use rectangles for both, there is a consistent way to tell them apart. In UML, the general form for an object declaration is

objectName : className

For example, chkTrans:Transaction indicates that we have an object named “chkTrans” of type “Transaction”.

Quite often, we know we want to discuss an object, but don’t really care to give it a name. For example, in all of our use-cases so far, there has been only a single checkbook. We know that it will be a member of the Checkbook class, but if we actually give it a name, the reader will think that’s something they are supposed to remember. Then, if we never actually use that name, we’ve distracted the reader for no good reason.

So UML allows to drop the object name:

objectName : className

as we have done for several of the objects in the diagram above, including the checkbook.

The colon (:) in front to the remaining name is our cue that

In essence, we have an anonymous object of a known class.

The dashed lines are called ``time lines”.

Or alternatively, a function call made by some code associated with the first object, calling a member function of the second object.

As with any function calls, these can include parameters.

Important Sanity Check: If you draw an arrow from one object of type C to an object of type T, and you label that arrow foo, then the class T must have a function named foo listed as one of its member functions.

An activation of a function is the information associated with a particular call to that function, including all parameters, local variables, etc.

Sequence diagrams are all about time, so we sometimes need to indicate just how long a function call is active (i.e., how long we are executing its body or executing other function bodies called from it).

Now, a sequence diagram indicates the flow of time, but it’s not a strict graph. We can’t say that one inch of vertical space equals some number of seconds. All that we can say is that if A is drawn below B, than A occurs after B.

Look, then at the applyTo call from the scorer to the rubric. You can see an activation box starting there, indicating the start of the function body of EssayRubric::applyTo. A little time after that, you see an arrow emerging from that box. That arrow indicates that this function body of applyTo eventually calls comcept.match(essayresponse). There you see another function body (of match) start to execute.

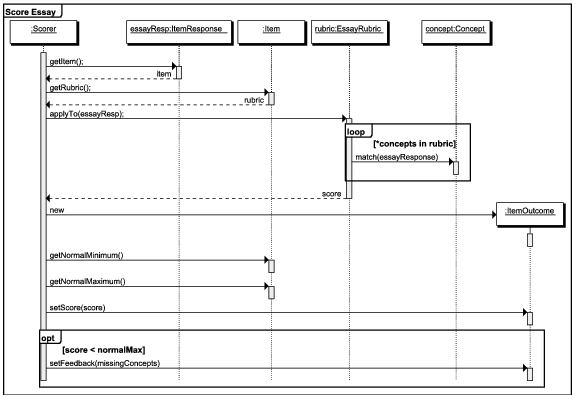

The particular drawing tool that I use insists on putting short activation boxes at the end of every call. If there are no further outgoing calls (e.g., getNormalMinimum()), these boxes are optional. A message arrow with no activation box on the end simply indicates that the function call issues no interesting messages of its own.

A function body that does issue a message must show an activation box so that we can see whence that message comes.

Sanity check 2: An incoming arrow to an activation box must connect to the very top of that box.

Sanity check 3: Every activation box must either

Sanity check 4: If a function body of foo calls a function bar, the activation box of bar must end above the end of the activation box of foo.

That’s just the way functions work.

Sanity check 5: If an activation box has an outgoing "return value" arrow, that arrow must emerge from the very bottom of the box.

Sanity check 6: If an activation box has an outgoing "return value" arrow, that arrow must point back to the caller of that function activation.

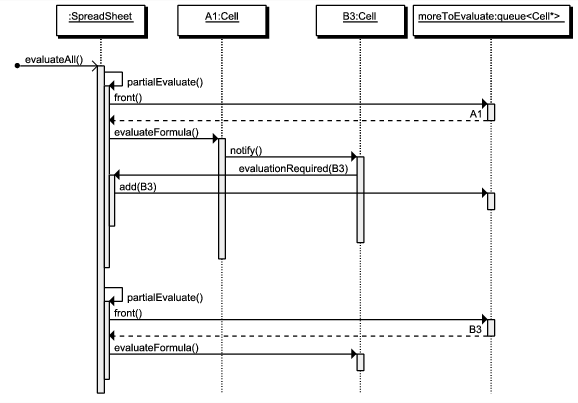

Activations Overlap (nest) in Time

The call/activation box symbols can easily accommodate simultaneous activations of different functions on the same object.

Observations:

Personally, I find the extra arrows distracting and don’t recommend them for general use.